"When do I need to replace my regulator?"

These are the kinds of questions we're often asked about specialty gas regulators and change over manifolds. And happily, from the maintenance to testing, we've got the answers that should help clear things up.

"What do I need to do to make sure my regulator or changeover manifold is working properly?"

"What regular maintenance should I be doing?"

A regulator (or changeover manifold) can last several decades if properly taken care of. This means keeping many things in mind on a regular basis, including: changing the cylinder to prevent pressure slam of the diaphragm; never dropping the regulator; keeping impurities or foreign particles from getting into the gas service; and protecting the pressure-reducing devices from the elements.

But in reality, operators don't always follow these guidelines and their regulators tend to fail. And while the pressure-reducing device typically does not give you a warning when the unit is going to fail, there are ways to inspect the device to make sure it is working properly and it's important to be aware of them.

One common issue is gauge failure, typically from seat failure or as a result of the regulator being dropped. It's easy to tell: the gauge will be pegged and may also contain water. In either case, the gauge needs to be replaced. In cold climates, the water could freeze, causing the bourdon tube to rupture and gas to vent to the atmosphere.

Seat failure happens as a result of particles getting into the regulator. This will cause the downstream pressure to equalize with the inlet pressure and the outlet gauge to fail. This should not be confused with Supply Inlet Effect, which you would see in single-stage regulators. To understand more about this, please refer to our publication The Chromatographers Guide to Gases and Gas Delivery Systems.

Specialty gas regulators have metallic diaphragms, so not backing out the pressure adjustment knob before connecting a new regulator can cause diaphragm failure. If the regulator is left in the open position, pressure will rapidly hit the metallic diaphragm and can cause crease and deformation. This will result in loss of sensitivity and possible diaphragm failure. When a diaphragm fails, gas will vent through the bonnet vents if either the diaphragm seal is broken or the diaphragm breeches. Bonnet vents should always be open and checked to make sure they are not plugged. This port must be open for the diaphragm to operate correctly.

The pressure-reducing device should be visually inspected at each cylinder change out. The operator of the device needs to inspect the regulator, the gauges (pressure indicators), valves, inlet connections and outlet connections for any obvious defects, or dirt or grease on the CGA. If there are any defects the product should be taken out of service and repaired or replaced.

After the visual inspection has been completed the regulator can be connected to the cylinder and pressurized. Then the operator can do Performance Pressure Test 1. During this test the operator inspects the function of the outlet gauges by rotating the pressure reducing valve's knob. The operator needs to rotate the knob counter clockwise to reduce the outlet pressure when delivering gas or venting the gas. The operator will need to verify that the gauge is responding to the change in the pressure setting by seeing that the gauge pointer drops. Don’t forget to reset the application pressure back when completed.

The next test to verify that the pressure-reducing device is working correctly is Performance Pressure Test 2. This test will require the operator to close the source pressure valve (cylinder valve) or inlet valve to the pressure-reducing device. The operator will observe to see if the inlet gauge pointer decreases in pressure when the pressure-reducing device is delivering gas to the process or when the gas is being vented off. If the gauge pointer starts to decrease, then the operator can open the source valve slowly and resume normal activities.

If in neither of these performance tests the gauge pointer does not move, then the pressure-reducing device needs to be removed from service and inspected by the manufacturer.

Another field test that an operator can perform on a pressure-reducing device is a Leak Check. When the pressure-reducing device is under pressure (both the high side and delivery side), the operator can use an approved leak test solution. SNOOPTM is not an approved leak solution in high-purity applications—Airgas recommends an ammonia-free solution instead. If a leak is detected, shut down the gas source, reduce pressure to atmospheric and tighten the leaking connection (do not try to tighten any fitting while the pressure-reducing device has pressure inside it). Once the detected leak area has been identified and addressed, the operator can repeat this test on other areas of the pressure-reducing device.

The final test a field operator can perform on the pressure-reducing device is a Creep Test. For this test the operator will need to close the outlet valve or a downstream valve from the pressure-reducing device and the inlet source valve. This will isolate pressure in the pressure-reducing device. The operator will need to visually watch the outlet gauge of the pressure-reducing device for two to five minutes. If the gauge pointer starts to rise and does not stop after two to five minutes, then creep is occurring—which means the inlet pressure is leaking across the seat of the pressure-reducing device, trying to equalize the pressure coming into the device to the pressure going out of the device.

At this point, the pressure-reducing device needs to be removed from service and either replaced or repaired. If the gauge pointer does stop and level out at a pressure a few pounds above the starting pressure, this is called Lock Up and is common in the regulator. When the gauge pointer levels out, the operator can reopen the source valve and the downstream valve to resume operations. This short test will give an indication of gross failure of the seat. An overnight test will show smaller leaks and sometimes is better because it gives an early indication of issues with the seat.

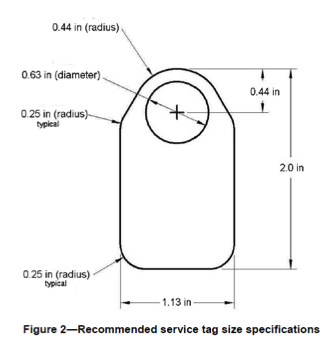

The specialty gas industry follows the guidelines posted by the Compressed Gas Association (CGA). In 2011 CGA updated pamphlet E-15 Periodic Service Program for Industrial Gas Regulators. In this pamphlet, CGA states that “Regulators do not have infinite service life, and they require periodic maintenance. Materials used in regulators, particularly elastomeric or rubber materials, will deteriorate over time. Aged elastomeric materials may exhibit hardening, stress cracking and other physical property degradation.” The pressure-reducing devices used in the specialty gas industry have elastomeric seats, such as materials like PCFTE and PTFE. CGA indicates that after a period of time (e.g., five years), these regulators should have their elastomeric parts replaced. As part of their recommendations they also state it is good practice to label the regulators with their in-service date. (See the graphic below from CGA E-15.)

You should never change gas service or CGA as there may be issues. CGA connections are specific for gas and pressure. When you change a CGA the new gas may not be compatible with the materials used to make the regulator or the CGA pressure rating may be higher than the MAWP of the regulator.